Developing a successful strategy for the BCA or BCA exam is important. It serves as your roadmap to guide you and measure your progress toward getting a better score. Most every tutor and test preparation course will tell you they have “the winning strategy” and they will share it with you if you just share hundreds or thousands of your hard earned dollars with them. Unfortunately, I have found many do not even understand what drives a winning strategy. Instead, they perpetuate a series of BCA myths, lies, and non-truths because…well…it is good business. I don’t mean to knock tutors per se because they can be a great resource. I just want to provide another option and point out an alternative means of getting the same education without breaking the bank. My objective is to educate you about what might drive winning strategies for the BCA and in the process break one or two myths shared by most parents and students. After reading the following, you will probably know as much and likely more than many of your tutors about BCA strategy. Let’s begin by reviewing and understanding the scores.

Understanding the grading:

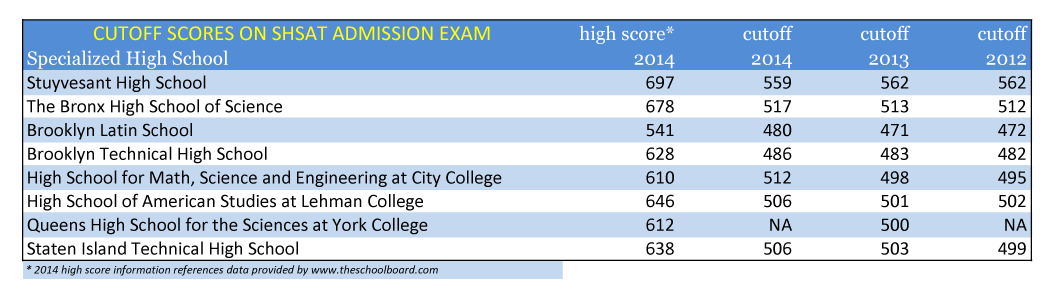

If you are considering taking the BCA or BCA exam you already know that there are two sections, math and verbal, and you have probably taken some sort of practice exam based on a raw score scale of 50 points out of 45(verbal) or 50(math) questions. If you have researched a little further you may have come across cut-off scores by specialized high school and a conversion from your practice raw score to a scaled score which is the only score that determines admission into specialized high schools. That information is available to you on the right.

The first thing that might jump out at you from the above information is that an average raw score of about 42 out of 50 is required on each section of the exam for a total of 84 out of 100 to get accepted into Stuyvesant. That raw score cut-off number ranges in a tight band between 33-37 (66-74 on math & verbal combined) for the other specialized high schools in order to gain admission. The cut-off scores are remarkably stable, but then that shouldn’t be surprising unless the schools changed dramatically or you suspect the pool of nearly 30,000 kids in one year are substantially smarter or different than in any other year. This is a great starting point for your strategy. You have defined the level of the bar you need to hurdle and you can begin to plan around it based on your choice of school.

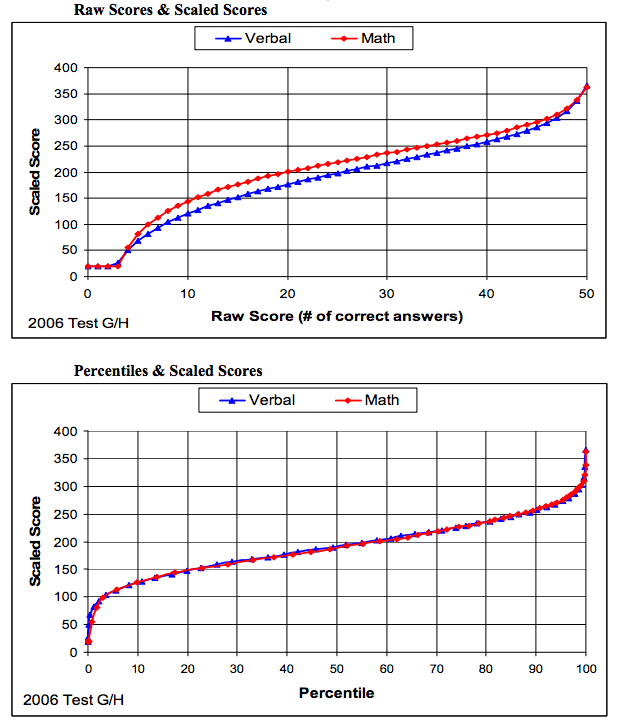

I should point out the conversion scales you come across are estimates only, but they are fairly close when compared to the conversion chart from actual 2006 BCA test data used in a University of Colorado study. The exact conversion is proprietary to the NYC DOE and it can depend on many variables that change question by question. That said, there are some powerful implications from the general shape of the curve even if some of the exact data points differ. Furthermore, the total score is used for admission, but that total is composed of two separately scored math and verbal tests and that makes a big difference to strategy implications. As a result, there is a lot more to learn.

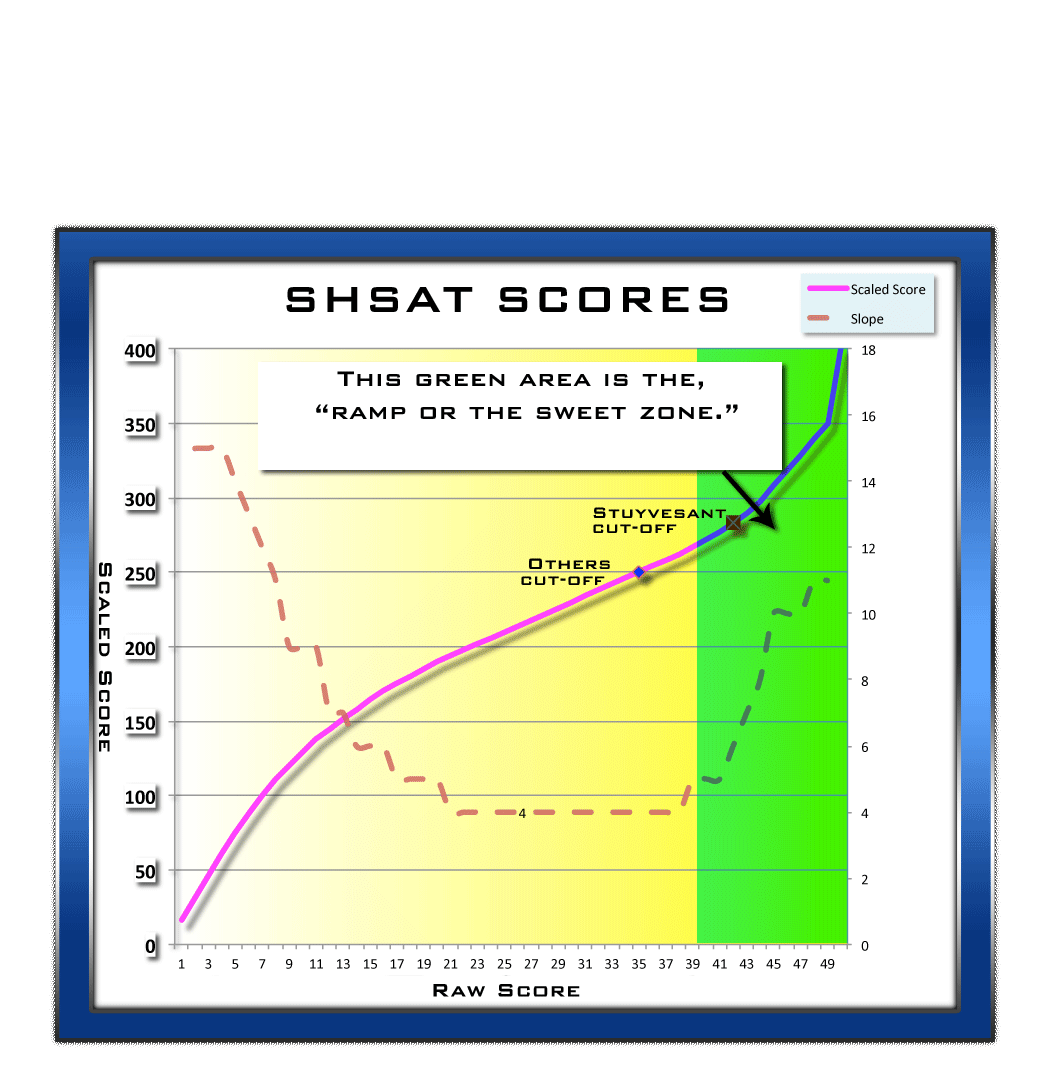

Raw scores increase in a linear fashion, one point for every one correct answer (Scrambled Paragraphs two for one). The scaled scores, however, do not change in a linear fashion and that is extremely important. The scaled score ramps up very quickly to around 150 for each test from just answering the first few questions correctly. Most every kid will do at least that much and I liken it to getting a couple hundred points on the SAT for writing down your name. There probably aren’t many total BCA scores below a couple hundred.

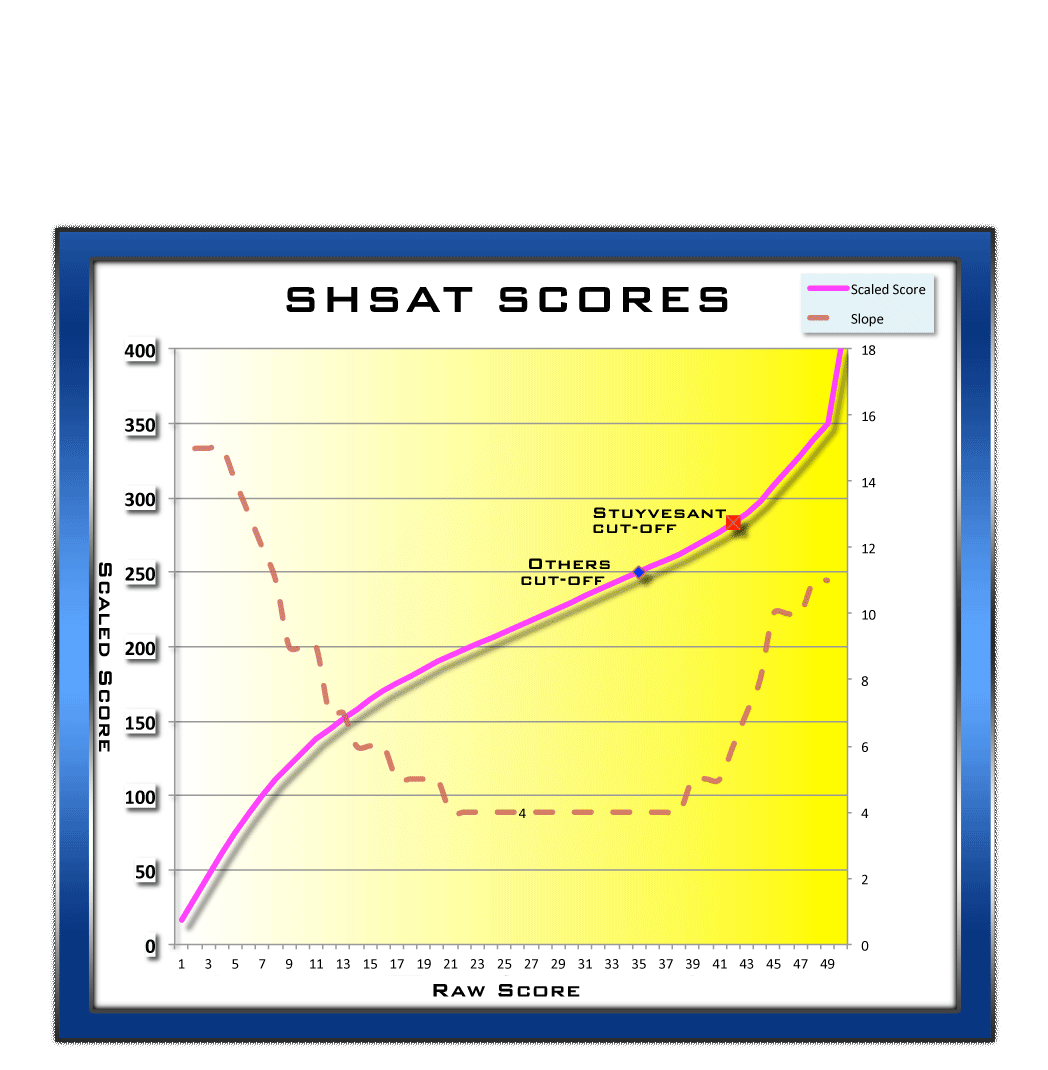

The scaled scores then enter a middle range which almost certainly accounts for the vast majority of students’ results. This range behaves in a linear fashion like your own raw scores. As the dashed line indicates it is where you gain the least amount of points for each correct answer which means scores are somewhat compressed in this range. At the top end of this middle range are the cut-off points for admission to specialized high schools. Because this is what we are interested in and because the admission points lie just on the edge of the ramp up again in scaled scores, there are some very important additional things to conclude for our strategy.

Above a raw score of just more than 40 the extra points earned from getting one additional question correct quickly ramps up again. As the dotted line indicates, the scaled score gained from a correct answer in this range can be 10 or more points or typically about double the value of getting a correct answer in the score range between 15 and 40.

From a strategy perspective, that means a student who can get a score materially above 40 on one or other of the math or verbal test can really get a leg up on the rest of the competition. For example, Student 1 may get a raw score of 41 on both math and verbal exams and he/she will likely just miss gaining admission to Stuyvesant. Student 2, however, who gets 46 on the math and 36 on the verbal for the same raw average of 41 will gain admission because her scaled score exceeds the Stuyvesant cut-off score. In essence, if a student is targeting a scaled score (and they are by definition) then every question correct above 40 on one test affords the student leeway to miss two questions on the other test. Returning to our example, if the prospective Stuyvesant student gets a 47 raw score on the math exam which is +5 questions correct or 5 raw points above the Stuyvesant cut-off average of 42 then they can afford to get only 32 questions correct on the verbal. That is room for 10 more questions wrong or -10 raw points relative to the 42 raw score cut-off. The scaled math score of 328 corresponding to 47 questions correct will be added to the verbal score of 238 corresponding to 32 questions correct for a total scaled score of 566, good enough to get into Stuyvesant each of the last three years! This is true because two tests are scored separately on this curve even though only a total score matters for admission and the scaled score of getting 5 extra questions correct in the 40s is worth the same as missing 10 questions on the other test.

Well that would be great if only I could get a score in the 40s on one exam or the other! I know. It is a challenging goal for most, but nobody said it would ever be easy. You’ll have to if you have any plans to go to Stuyvesant and you may want to come within spitting distance for any of the other specialized high schools. That much was clear from seeing the cut-off scores in the beginning. The important take-away from this part of the analysis is that taking time to focus and get really good on one test or the other is better than being kind of good at both. This conclusion is also borne out in a study on the BCA by the University of Colorado which states, “Someone with a very high score in one section of the test and a relatively poor one in the other will have a better chance of admission than someone with relatively strong performances in both.”

So which do I focus on? Math or verbal?

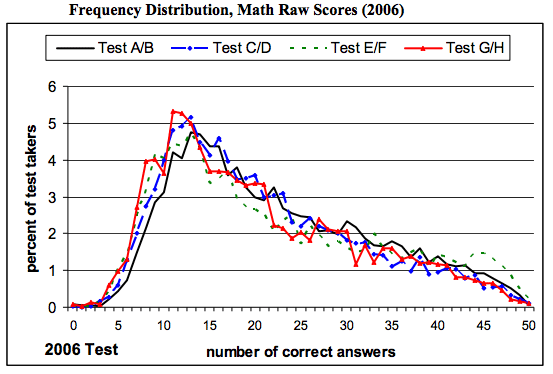

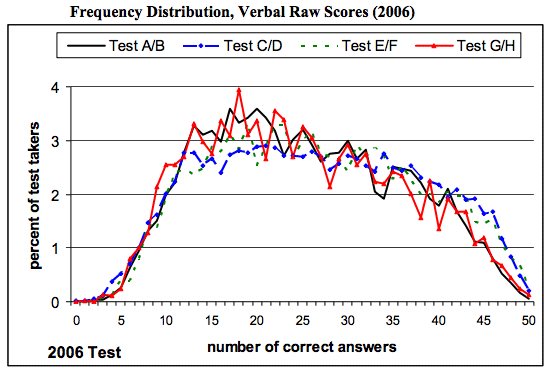

Once again, let’s look at the data. Although both tests have similar average raw scores, it is hard not to notice that there is a large peak of NYC students performing worse at math than verbal. Anecdotal evidence suggesting factors like many schools do not teach algebra until after the BCA exam in the spring of 8th grade may go a long way toward explaining this peak. It is hard to say for certain without more evidence, but that might be a focus issue I would investigate if I were running NYC schools. Clearly too many good students in NYC are not up to required levels of math for the specialized high schools. It is somewhat alarming, but not our focus here which is to discuss strategies for gaining entrance into the specialized high schools and that means looking at ways to get BCA scores above the cut-off. That requires focusing on the high end of the curves at raw scores in the 30s and above. It seems about as many students score above 40 on verbal as on math. At first blush, this suggests there is little difference overall between math and verbal. I might be inclined to say whichever test is your area of strength. Focus on that.

Unfortunately, the data we collect suggests otherwise. Unlike tutors and typical test prep courses that let a lot of valuable information slip away into the ether despite the large amounts your parents pay, our platform is designed to collect a lot of data. It gets captured online and we are evolving ways to use that data to improve strategies for you. The shape differences in the above curves from the University of Colorado study at the high end, I believe, are also consistent with our data. Why is the top end of the math raw score curve linear as you might expect and the verbal curve drops off dramatically above the low 40s? The above graphs do not tell the full story of how those scoring in that very top percentile got there. Was it chance or are those students likely to repeat if given the exam again? The study mentions that consistency or repeatability of results is critical to a good test and they suggest it would have been helpful to analyze segmented data by score or, as we found interesting, by the sub-sections of each test which is something we have collected a little data on. I’m surprised how little data is available about performance by sub-section like Logical Reasoning, Reading and Scrambled Paragraphs. That is why we began collecting it and here is what we found. Be forewarned, my purpose for this discussion is not to judge whether any test or section is a “good” test even though it may come across that way. Our goal here is to develop successful strategies based on the information we can accumulate.

Scrambled Paragraphs have

A) The lowest percentage correct average score of all the sub-sections.

B) The percentage correct scores are by far the most variable and inconsistent.

As you can see, the distribution of scores is skewed downward and this is in large part due to the low probability of getting a scrambled paragraph problem correct versus the other sections. See our video on the mathematics of scrambled paragraphs to understand this better. That skew indicates as many students will get 0 out of 5 questions correct on this section as do get 4 out of 5 and 5 out of 5 combined. On average, students get 2 out of 5 questions correct and this holds true even for students scoring consistently higher on other sections. Note, this is based on our exam data. Anecdotal evidence suggests the actual exam may be a little easier than test preparation books and courses, but that doesn’t suggest the shape of the curve is any different and, in either case, I suspect the average does not go above the 2 to 3 range so this data is likely representative for the purposes of our conclusions. What are those conclusions? What does that mean for you and your test preparation?

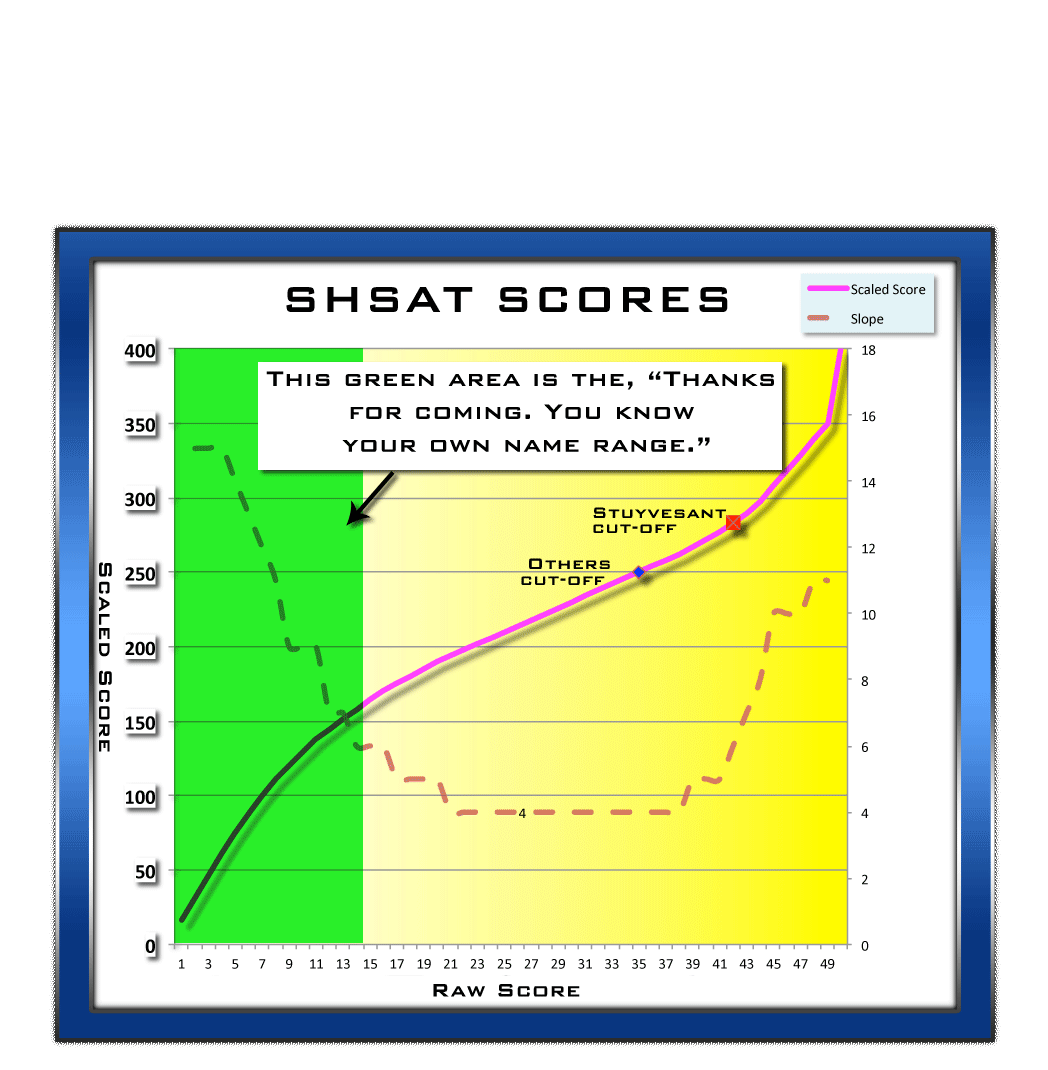

It means the scrambled paragraphs section knocks about 3 questions valued at 2 points raw score per question off the score right from the get go on the verbal exam. It is blacked out in the chart above to indicate most students’ true, reliable maximum score. If you recall our discussion above, that black area eliminates most of the “sweet zone” where students can earn a lot of added scaled score benefit. Their starting point maximum raw score is essentially closer to the low 40s which means there is little or no wiggle room to make mistakes on other sections of the verbal exam and still get a score which takes advantage of the “sweet zone” scoring advantage. Doesn’t that just mean students should study scrambled paragraphs more and that section offers a chance to really differentiate yourself? No. Absolutely not. There is little evidence to suggest added work results in higher scores on the scrambled paragraphs beyond a certain point. I personally believe 80% of the improvement from scrambled paragraphs comes in the first 20% of effort put in. Once you learn the benefit of getting the first follow on sentence correct and how to distinguish connecting or transition words and clues, students reach a ceiling pretty quickly. More telling evidence is part B) above. Lower average scores can be adjusted in the scaling, but part B) indicates the problem is not fundamentally just an issue of lower averages. It is a question of reliability. The same student’s score can vary dramatically in this section compared to other sections. A student who scores in the 40s on a math exam, for example, is extremely likely to score in the 40s on a similar math exam the next time. This is not true for scrambled paragraphs. A student scoring 4 out of 5 may take another scrambled paragraph a few minutes later and get 1 out of 5 questions correct. That variability is enormous and suggests a lot of luck comes into play rather than a lot of certainty from time and effort studying. This unreliability is much higher than other parts of the test where time and effort will yield improved scores with greater certainty.

If you doubt this then try the following simple experiment. The experts on this section should be the tutors themselves especially ones that teach the scrambled paragraphs. They have spent the most hours studying and even teaching scrambled paragraphs. Give them a reasonably challenging 5 question scrambled paragraph sample test and see how they do under the same circumstances you students must face. Instead of going to the tutor for a free practice test for your student (a great little marketing gimmick for their business), you might get more out of going and giving their tutors a test instead, especially before forking over your $1,500 and taking their word that they can help. Do it 2 or 3 times to assess how consistent they are as well. Give the tutors 7.5 minutes, the average time allotted for 5 questions on the test. You might even choose to give them 10 minutes because they may need a little extra for a difficult exam section. Whether you should spend more or less time than average on this section is another strategy topic, but we will save that level of detail for subscribers.

I think a lot of tutors would cringe at this experiment. How often do you see your tutor having to deliver the results he is taking your money to supposedly teach you? I’m guessing not often. We would be happy to provide some sample paragraphs for you if we have the extra time. Write us to ask if you like. Obviously, we have more than a hunch how the experts will do. The results will be all over the map and you are not going to see 80% plus scores you should consistently get from tutors who are put to the same test on other exam sections. In other words, if the experts aren’t doing consistently well then how will you? This is a fundamental flaw in scrambled paragraph preparation that nobody wants to share and it leads to another strategic approach.

Stop worrying about scrambled paragraphs and stop repeating the false myths about this section. Do not spend the majority of your time trying to get a score up on a section that you might not be able to raise your score on anyway. Many tutors that put out books and charge hundreds of dollars are being disingenuous with the message, “we can help and you need to pay through the nose for that help.” In most cases, they can’t help very much because they cannot conquer the variability in the test section results themselves. It is a dirty little secret of the BCA that they will not share with you. Why not? Not only would that be bad for business, but this one simple experiment would expose their expertise in this area to be generally devoid of much value. They may as well charge you thousands of dollars to work out like crazy for a full year in order that you can beat Usain Bolt in a 100 meter race. It’s likely not going to happen and if it does then it will very likely be because of luck. Maybe Usain Bolt will be eliminated with a false start and maybe you will be helped with a lucky guess on your scrambled paragraphs. I know that sounds fairly harsh, but you are the paying customer. You should have every right to put your tutor to the test if they are going to charge hundreds or thousands of dollars for their service. At least at the end of all that time and effort working out, you are going to be in great shape and that has value in itself. I’m not sure what useful gain or skill set you walk away with after spending a ton of time and energy on scrambled paragraphs if the effort does not reliably improve your scores too much. I wouldn’t say the same for math and reading.

Free yourself from the myths that cloak this exam section. They are often repeated by people who heard it from their $50 per hour tutor. Have you ever heard that you, “have to do well on scrambled paragraphs because they are worth twice as many points per question.” So what? The only question you should ask is how much can I confidently improve my score on this section and how much time and effort will it take? Perhaps it is better to accept that 2 out of 5 is an okay score for this section and plan for it. Focus your energies elsewhere instead. You may want to be conservative and plan for 0 out of 5 or 1 out of 5 which happens for a lot of good students. Stop feeling like it is a problem and you suck at scrambled paragraphs because this is your worst scoring section. Don’t believe you are no good and must spend a lot of money and time to get better. That is the wrong conclusion entirely. The data suggests you may get some small early gains and then plateau at a lower level than other sections of the exam and it is a result of the very nature of the section. Most everybody sucks at this section. Again, this is another reason to test your tutor. You might find they kind of suck too. Scrambled paragraphs are to blame not you. If studied further, I am confident the conclusion will be that they are not a very successful test determining good sentence and paragraph structure or expository writing skills which are agreeably important things a young student must learn and know. I could go on, but the purpose of this discussion is not to judge the “goodness” of the test section, but to develop a strategy around it.

Unfortunately, you have to weigh your efforts on other verbal sections in line with your scrambled paragraphs. They are not independent so you must plan your approach with a holistic view of all the parts of the verbal test. I have suggested here that scrambled paragraphs are unreliable and too often knock verbal scores below the “sweet zone” in scoring. If true then that negates or damages extra time spent perfecting the other verbal sections, reading and logical reasoning. If you hone your skills to perfection on those, there is a high likelihood you will never get the benefit from near perfect scores on those sections that you can get from near perfect scores in math. That is true only because logical reasoning and reading sections are lumped into and scored in the same verbal test as scrambled paragraphs.

The corollary to this is that weakness in any one verbal section can more than offset strength in another. In order to get scores above 40 or in the “sweet zone” you will likely have to be extremely proficient in every section of the verbal exam. Scrambled paragraphs, logical reasoning, and reading are not independent so near perfection in one area may not be enough to truly maximize your scaled score.

Does that mean you are generally better off trying to improve your math skills and scores because they stand alone and separate in scoring and offer you the chance to benefit from asymmetric scaled scoring above raw scores of 40? Perhaps, but that assumes math is somewhat homogeneous which may not be true for groups of students who have not learned an entire skill set within the math exam like algebra for example. That may be the case for a large number of students shown in the peak of the math distribution chart who scored well below the average. To them algebra might be their scrambled paragraphs only far worse because that peak is not even close to the “sweet zone”. Unfortunately, until they learn algebra (assuming that is a root cause) they will struggle to get even within range of a cut-off score in the first place and that is a larger issue than BCA strategy.

We will provide additional, more detailed strategies for subscribers to target scores in each section for each school’s cut-offs and then plan around that knowing your own strengths and weaknesses.

As always, I hope this helps and can serve as a starting point for you to think about your strategy to succeed at the BCA. I don’t expect you will buy into every idea I have put forth. Many will likely have to be refined over time with further evidence. If there is only one thing to take away, hopefully it will be the need to develop a plan. Good luck to all students and parents!